This post mainly serves as a reminder for myself as to how JS code is handled once it is run inside the browser, but if it happens to help others as well, that would be great.

Java Script (JS) is a non-blocking and single threaded language originally designed to create better client side web applications and to be understood only by browsers, and as a security measure, it would have no access to local system resources such as the file system and low level hardware. However, technologies such as Electron and NodeJS can allow JS to be used to create desktop or server side applications.

While JS and NodeJS share the same language, their areas of implementation differ.

But we’re here to talk about the original JS runtime environment, so let’s get to it.

The typical JS application consists of native language APIs, the JS engine, and Web APIs provided by the web browser that JS runs inside of.

JS can be compiled on various flavours of runtime engines, such as Chrome’s V8, Firefox’s Spider Monkey, Edge’s Chakra, etc. Those engines in turn are embedded inside of their respective browser products. Which offers respective Web APIs that expose additional functionality, such as AJAX requests and timeout functionality.

When your JS code gets compiled, it will go through one of the above components.

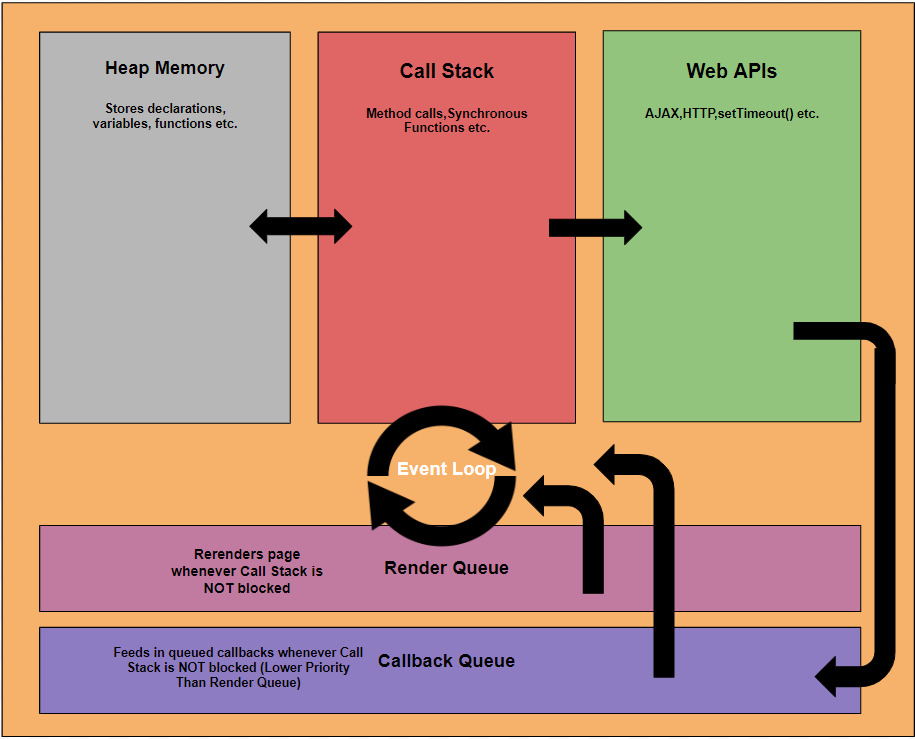

When JS code is compiled by V8 for example, its contents will be put into the various areas depicted in the diagram above.

Heap:

Variables and function declarations go into the heap memory, which is an area of unstructured memory that holds information ready to be used.

Stack:

Function calls are then put into the stack in the order they are called in the original JS code, once a function is executed, it will be removed from the stack and the next one in line will be executed. By this principle, if a function such as a database query takes a long time to execute, that would technically block the execution of the rest of the code, which would lead to frozen UIs and crappy UX. But fear not, functions like these are put into a separate line of execution. The web API queue.

Web APIs Queue:

Browser provided functions such as AJAX, HTTP, and setTimeout() are asynchronous functions and will not be completed in a reasonable amount of time, thus messing up the execution flow in the stack if not separated. To address that, these async functions are put into the web API queue to be executed no matter the order, once any of them received a response, the results are put into the callback queue.

Callback Queue

Completed Web API requests are put here in the order they are completed, and will be sent to the event loop whenever the call stack is free. This queue however, has a lower priority compared to the rendering queue, which will send a render request to the call stack before each callback.

Event Loop

The event loop checks if the call stack is empty and adds render jobs and callback jobs to it.

Rendering Queue

The rendering queue is what updates the UI around 60 times per second, if call stack jobs are not cleared, then the render jobs cannot be inserted into the call stack, thus freezing the UI. By alleviating asynchronous callbacks into the callback queue, the rendering queue has a higher priority than the callback queue and will be able to update in between each callback job, thus making the UI still available for redraws and the user experience consistent.

#

If any of the above is not clear, feel free to refer to this wonderful site created by Philip Roberts which provides animated sequences of the JS runtime that will sure to clear out any confusions.